Ordinary People opened the door.

It was an ordinary Saturday——a brisk, clear fall day, the red, gold, and orange leaves on the trees shimmering in the brilliant sunlight. . . .

Towards evening on that ordinary Saturday, Bob and I went to see Ordinary People, which was playing at the movie theater on Cedar Lane——the main artery running through downtown

Teaneck. . . . I didn’t know much about the movie, only that it was Robert Redford’s directorial debut, had an all-star cast, and had received excellent reviews. . . .

As I watched, the internal agony the main character, Conrad Jarrett (Timothy Hutton), is going through felt achingly familiar. Shortly after the movie begins, the viewer finds out that Conrad’s older brother, Buck, died in a boating

accident. . . .

As I sat next to Bob in that darkened theater, my face and body began to sweat. I felt a shock of recognition. Although the particulars were different, I knew what Conrad was feeling—-or rather not feeling.

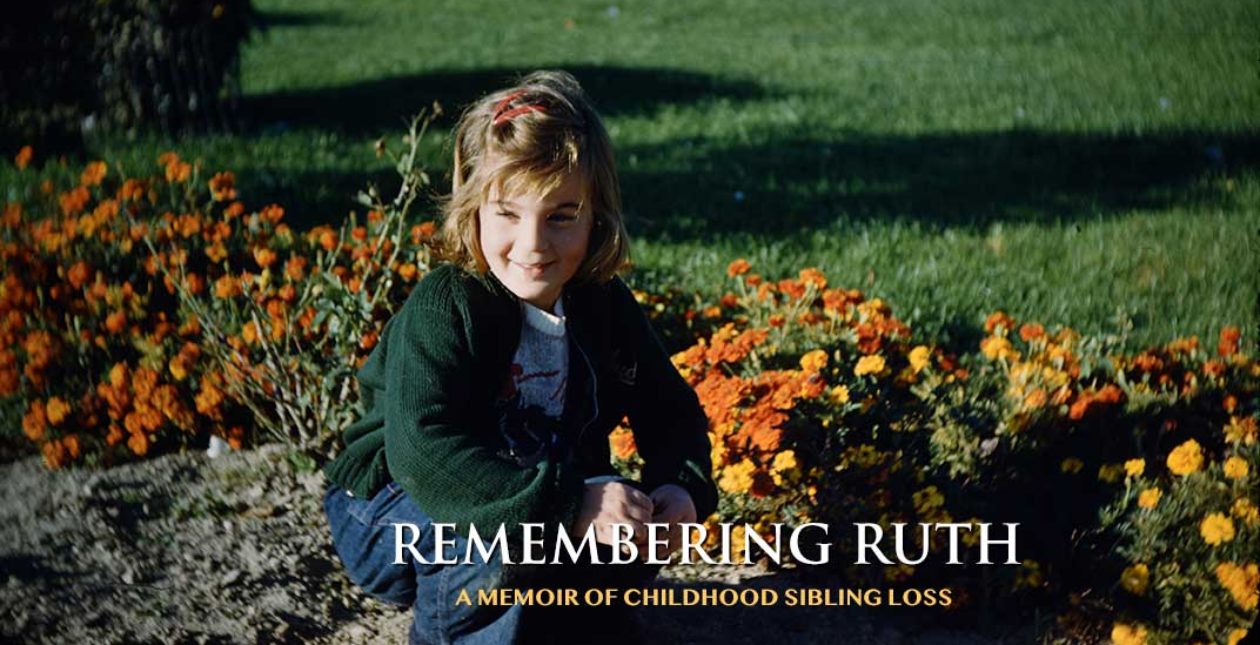

I had entered the same unchartered territory after Ruth’s death. . . .

I felt like a wet dish rag when the movie ended. I had cried more tears into more tissues in those two hours than I had in the last twenty years since Ruth’s death. . . .

Ordinary People opened the door. I knew I was hurting in every fiber of my body, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. My sister had died decades before. It was time to confront the pain and work through it.

Group therapy seemed like a great idea in theory,

but the reality terrified me. How could my needs be met when there would be four others vying for her attention?

With each passing week, I began to express more of how I felt. I became more aware of my anger, and understood that I had as much a right to be angry as anyone else. It took a long time to get there, and it wasn’t easy sailing.

A big piece of it was how angry I was at Ruth.

Why did you have to die? I wanted to know. You were my champion, my playmate, my best friend and confidante, my ally in our family, and you deserted me. . . .

As I began to express these feelings, I found I wasn’t just angry, I was furious. The feelings had been locked inside me for more than twenty years, and I’d never wanted to face them. They weren’t nice feelings, and having them made me a pretty horrible person, I thought.

I began to have panic attacks and depression.

I lost my appetite and picked at my food. I rapidly became almost dysfunctional. Some mornings I couldn’t get out of bed, and I missed days at work.

I called Harriet (my group therapist) several times between group sessions, and talking to her helped at first. But soon I couldn’t bounce back. She said I needed to take an anti-depressant.

“I don’t believe in medication,” I told her. “I don’t like to take anything that isn’t natural.”

“You’re feeling this way because you’re making progress, and in the process you’re stirring up some strong feelings,” she said. “So you have a choice: Take the medication to help you move forward, or don’t take it and stay where you are.”

She was right. “Okay,” I said.

A Hunger to Read Articles on Childhood Sibling Loss

Being in the group helped me realize that having a sister who had died when we were growing up was significant and had had a huge impact on me, and that it was okay to have conflicting feelings about the loss. . . .

I accepted this intellectually, but I was not yet able to emotionally.

In addition to what I learned there, I had a hunger to see whether articles or studies had been written on the effect a child’s serious illness and death had on siblings. . . .

. . . .I decided to do some research at the Fairleigh Dickinson University library in Teaneck. . . .

Literature on sibling illness and loss was sparse, but what there was validated my own feelings. I was particularly interested in reading about the effects on siblings of a child dying following a prolonged catastrophic illness. Several mentioned anger toward a sick sibling that the healthy child often feels but buries deep inside, expressed in wishing the child is dead so things would get back to normal. The well child can also feel jealous of the sick one getting so much of their parents’ attention. . . .

As I pored over the articles I had found, I felt a new sense of relief. I’m not alone, I thought. What I’m feeling is okay. . . .

Negative self-image . . . worries about your own

health . . . high anxiety . . . keeping thoughts and feelings to yourself. I wasn’t the only bereaved sibling who had reacted in these ways!

Listen up, everyone! I wanted to shout. I’m okay——just a little crazy, and mixed up for more than twenty years because my sister was sick her whole life and died when she was fifteen.

Attending a Retreat for Bereaved Siblings.

The range of feelings I’d had since Ruth died were validated by professionals who had studied sibling loss. . . .

But soon I realized that squirreling myself away in a library, reading articles about the effects of sibling loss, wasn’t enough. I also had an overwhelming desire to meet others who had lost a sibling when they were growing up. . . .

I was a novice when it came to the computer, but I punched in sibling loss. To my amazement, Rothman-Cole Center for Sibling Loss popped up. It was based in Chicago.

. . . I picked up the phone and dialed the number.

“Hello,” said a woman with a pleasant voice,” how can I help you?”

. . . My sister died over twenty-five years ago, and I’m just beginning to deal with the loss,” I told her. “I’d like to meet other people who’ve had a similar experience. . . .”

“. . . In two weeks The Compassionate Friends is holding a weekend retreat for bereaved siblings in Kansas City,

Missouri. . . .”

The Compassionate Friends. . . . I didn’t want to have anything to do with bereaved parents. . . . My parents were enough to handle. I didn’t need to get involved with a whole organization devoted to people who had lost children. But a weekend that centered around sibling loss——that was a different story. . . .

Once I was there, I got very nervous. I didn’t know a

soul. . . .

By the time I left the conference, I had the names and addresses of a number of people I had met. Two of them had started sibling-loss support groups through their local Compassionate Friends chapters. I was seeing the organization in a whole new light. . . .

It was another step on a journey we never wanted to take. That weekend we discovered that meeting others on the same journey made our loss easier to bear.

“Something is really wrong. I think I’m too overwhelmed.”

I was trying to fall asleep the first night of the Weekend Grief Recovery Group . . . sponsored by the Rothmans-Cole Center for Sibling Loss. When sleep eluded me, I began a journal in which I expressed my frustration.

The three-day experiential workshop was being held at a retreat center outside Chicago. . . . Jerry Rothman was leading the group. . . .

After dinner, we reconvened in the meeting room for the first of several experiential activities. . . .

“Find a comfortable space on the floor and stretch out on your back,” Jerry began. We did. “Close your eyes and breathe deeply while you listen to the music. As you relax and breathe deeper, you’ll begin to release a lot of feelings that are deep inside. . . .“

I began to breathe deeply, and as I did, I could begin to feel the music reach inside me. . . .

All of a sudden, I welled up and began crying uncontrollably. Swiftly, Fran (one of the therapists) was by my side. She took me in her arms and began rocking me back and forth while she whispered to me.

“I loved her s-so much,” I stammered between sobs. “Why did she have to die?”

Fran stroked my hair and comforted me as if I were a little girl. “It’s okay,” she said. “Let yourself feel the pain.” We rocked back and forth for some time. I trusted her, and I was able to let myself go.